New Hope resident Walden Martin, not only an avid gardener, but a part of history

Walden Martin belongs to a unique organization in Gilmer County, a group of old and new friends known as the ROMEO Club.

“Retired Old Men Eating Out,” said the man also called “Waldo” to those who know him well. He’s an interesting member of the circle, since Martin has a lifelong passion for gardening that has put food on many a table. In fact, he’s assisted other gardeners at the Gilmer County Cannery so often some folks think he’s an employee.

“I take everything to the cannery,” he said last month in his New Hope community home. “I’ve made soup, applesauce, apple butter — anything I can think of that I can ‘can.’ Everybody used to think I worked at the cannery because I was over there all the time; and if I wasn’t canning, I was over there helping other people.”

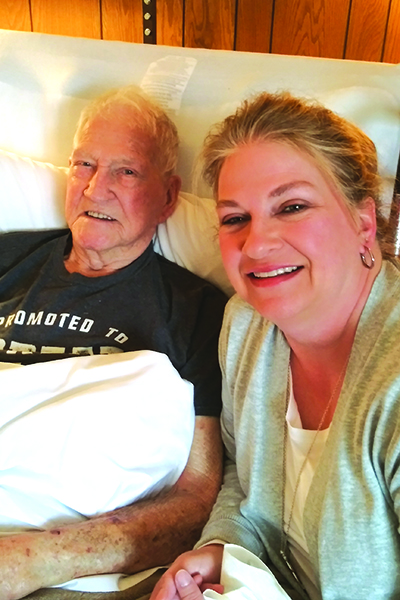

His daughter, Lisa Bradley, noted her father wasn’t a fixture at the cannery as much last summer since he contracted Covid-19 in July.

“He was in the hospital nine days, but not in ICU and not on the ventilator,” she explained. “He got better and came home, and in about three weeks, he was improving as far as his levels of oxygen. Then he started getting worse and feeling bad. At the end of August, he went back into the hospital and spent three weeks in ICU. He never went on the ventilator.”

Bradley noted Walden, 91, had lung cancer in both lungs 30 years ago.

“Covid did a number on his lungs, but right now he’s fine,” she said. “Now he goes to church about every Sunday at New Hope (Baptist). My mother, Kathleen, was the pianist there for years and years.”

Martin lived in Whitestone as a boy, and went to school in Pickens County.

“Half of it was in Pickens and half in Gilmer,” he said of the community known for mining. “Pickens ran a school bus up to Whitestone, but Gilmer didn’t run one down there. So there was about eight or 10 of us that went to school in Pickens County, but we lived in Gilmer.”

In 1946, he graduated Pickens County High in the 11th grade because there was no 12th grade for a senior year. But before graduation, there were some antics along the way.

“The roads were bad back then,” Walden said. “We had a big hill, it was muddy and the old bus was slow. It had a valve on the gas tank in under it. The bus would be in first gear, going slow, and I’d jump out the window and crawl in under the bus with it a-going and screw that valve off. Before we’d get to the top of the mountain, the old bus would stop. The bus driver would get out and start walking, going to get some help. We’d get under the bus and turn the valve back on, and one of the older boys would crank it up and go on and pick the driver up.

“He didn’t know what we’d done — he was an older fellow.”

But one day a prank backfired.

“We’d get down to Talking Rock, and have to come back up Highway 5 a quarter of a mile or less to go to the schoolhouse. One day I crawled up on top of the bus, and it just so happened the school superintendent was behind us. Oh man, I got tore up for that!” he said of the paddling.

“And he probably got it worse when he got home,” Lisa chimed in.

‘There’s a bear!’

But growing up, there were always vegetables to be grown.

“Momma always had a garden,” Walden said. “We grew anything we could eat. I remember Daddy, after we dug the potatoes, he’d dig a hole out in the middle of the garden and put straw in it. We’d put the potatoes in there and cover it up, and when we wanted potatoes Momma just opened up the hole and got them out.”

Although resting now to allow his lungs to get back in shape, Waldo knew in February spring was right around the corner. That means he has a hankering to be back in the dirt.

a couple of springs ago at almost 90 years old.

“I’ve got a big garden plot down there now — I can’t work it now, but I did last summer,” he said. “I’ve got an electric fence to keep the deer out. Years ago my son, Greg, went down there with his son (Garrett) on the back of a four-wheeler and said, ‘Now we might see a bear down here.’ Garrett didn’t believe him, saying, ‘Oh, sure, we’re going to see a bear.’ They went down by the fish pond and come back around and Garrett started shouting, ‘Daddy, there’s a bear! There’s a bear!’ There was a bear sitting over there, and he would reach out there and get a bunch of it and just pull it in to him, eating my corn.”

He still hopes to plant a garden of around an acre, and said even older farmers can learn new tricks — such as how to plant marigolds next to his 100-120 tomato plants to keep the bugs away.

“This past summer, I had three rows — 100-foot long each — of white half-runner beans, and had enough beans for at least three or four families to pick green beans — the best on beans I’ve ever done,” Walden said. “I wish I was out in my garden right now, getting it ready.”

Produce has included squash, cucumbers, beans, onions, tomatoes, potatoes, okra and beets. He also remembers taking the family’s corn to a mill west of the Highway 5 South and Industrial Boulevard intersection, across from the present-day Dairy Queen. He worked in the mines at Whitestone for around six years, and after that went to Lockheed for 39 years, making the commute each weekday.

“Daddy hauled riders (to Lockheed) in an old Country Squire station wagon,” Lisa remembered. “They’d meet at 4:30 or 5 o’clock in the morning, and he was known for getting you there on time. It didn’t matter if he got stopped by a state trooper or hit a deer, he would get you there. And if you weren’t there on time, he’d leave you. I remember a few times with him banging and hitting and slamming doors because he woke up late, and he knew he had to be there or they’d really give him a hard time.”

“We wanted to be on time for everything,” Waldo said matter-of-factly.

The Whitestone Flood

His memory is keen on the role he played in some of the historical events of his day, such as the deadly White-stone Flood of April 7, 1937.

“We lived kinda up high,” Walden said. “Me and a buddy spent the night there at the house, and it was a-raining so hard and the lightning was about solid so that you could see the water. The river got up and went in under a store. There were some cousins that swam across from the railroad track and tried to get those people to get out. They told the cousins they’d seen it get up under there before, so don’t worry about it.

“So they swam back out. Then that store washed away. There was a gas lantern setting on the counter, and when the store left, we saw that light going on downstream. It washed the store away — there was 13 people in it, 11 in the same family. They all drowned.”

Because the Martin home was on higher ground, there were more than 30 community members who showed up to eat breakfast the next morning.

“By the time they got into the house, they were wringing wet,” he remembered. “I ain’t never seen it raining like it did then. There were also waterspouts hitting the side of the mountain. It washed the train trestle away.”

The Pickens County Progress bears out the story, and published an article titled, ‘10 Disaster Victims Buried in One Grave.’ It noted a funeral service for all 13 victims in the store was held in the high school gymnasium. At the time, a 17-year-old boy was still missing and searchers were out looking for him. Walden said the boy was eventually discovered on a creek bank, and men had to smoke cigars as they recovered his body.

Disaster at Texas City

Later, but still a young man, Waldo served in the U.S. Army’s Medical Corps, stationed at Fort Sam Houston in Texas. While there, the Texas City disaster of April 1947 — where a ship loaded with ammonium nitrate caught fire and exploded in one of the largest non-nuclear blasts in history — killed 581 people near Galveston and resulted in scores of burn victims being sent to the Army base to be treated.

“A compartment next to that fertilizer was loaded with ammunition, and that thing blowed up,” Walden said. “One ship would blow up and catch another ship afire, then that one would blow up. It blowed the train and boxcars off the tracks. I was working in the hospital helping a nurse. I reckon I was her aide. Fort Sam Houston is where Brooke (Army) Medical Burn Center is, and that’s where they sent all the burnt people. That’s the reason we went down there, and big buildings were burning when we got there, and they were burning when we left after a week or more.”

These days, Martin is also telling others about a remarkable occurrence last summer when he was hospitalized when Covid caused fibrosis to set up in his lungs. Having had lung cancer twice — once in both lungs — but now being cancer-free for 25 years, plus being in two close calls with death in wrecks, he realized how blessed he had been.

“The Lord saved me twice, besides the cancer,” he pointed out, mentioning that one time his dump truck came within inches of colliding with a speeding train. “The Lord just took hold of me, and told me I wasn’t doing what I ought to be doing.”

“She (Kathleen) got the kids up and took them to church every Sunday morning, but there was a long time I didn’t go,” Walden said.

“He’s been telling a lot of people about it, and gave his testimony at church,” Lisa added.

Walden said his father, Robert Lee, told him many times, “If you’re going to do something and it’s worth doing, it’s worth doing right.” It’s a memory he’ll cherish as he once again looks forward to getting out in his garden this spring, stretching a string to make sure those 100-foot rows are straight.

(By Mark Millican, Home, Garden & Garage magazine 2021)