David Herendon was the fourth Gilmer County man killed in Vietnam

When David Herendon and his girlfriend split up, she asked his friend, Jim Logan, to intervene but got a wary response

“David was a good boy,” Jim said last week. “He was red-headed, and had a pretty high temper. He was going with a real pretty blond-headed girl and they’d broke up. One day she called me, and wanted me to take her to the drive-in (theater) to find David.

“I thought, ‘Oh me, I don’t want to do this.’ If old David saw me, we’d liable to get in a fight. I agreed to do it, but said, ‘I tell you what. You’d better tell him right quick you got me to do this.’ We went and parked at the drive-in, and David came driving up beside us. She got out, and that’s the last I seen of her. I was sorta worried about that, though. David would fight a circle saw — his brother Ronnie knows that.”

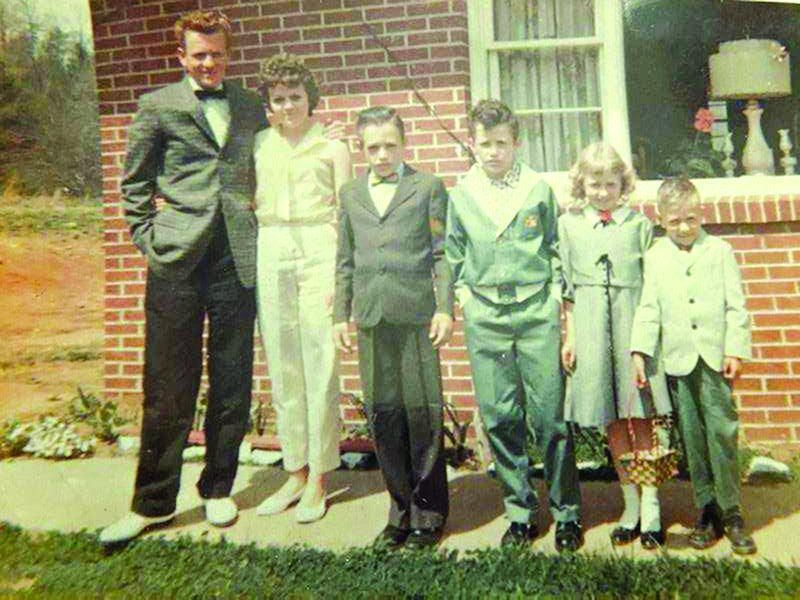

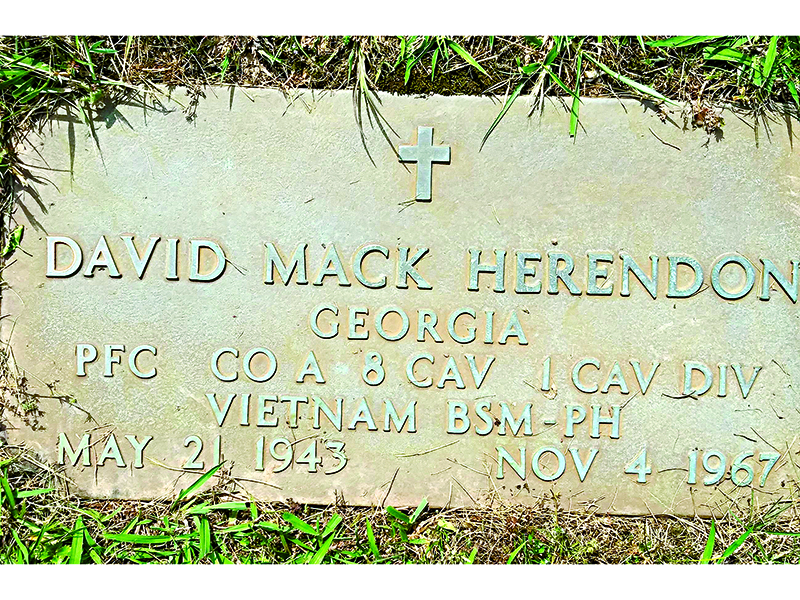

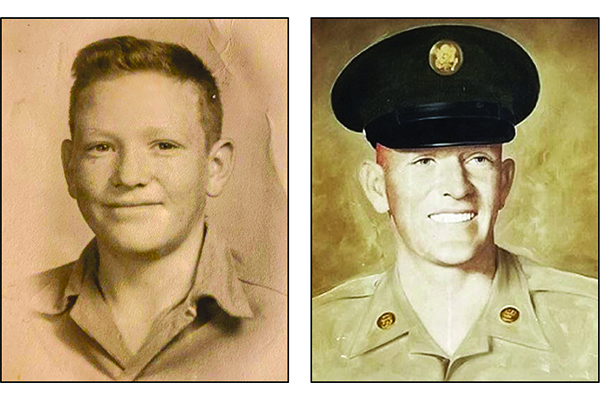

PFC David Mack Herendon, 24, of Cherry Log, was the fourth man from Gilmer County to be killed in the Vietnam War. He died on Nov. 4, 1967, the firstborn of Charlie and Ruth Whitener Herendon’s six children. Herendon was a member of Alpha Company in the First Battalion of the 8th Cavalry Regiment (the “Jumping Mustangs”), of the First Cavalry Division.

Ronnie said David was “more like a dad to me than a brother.”

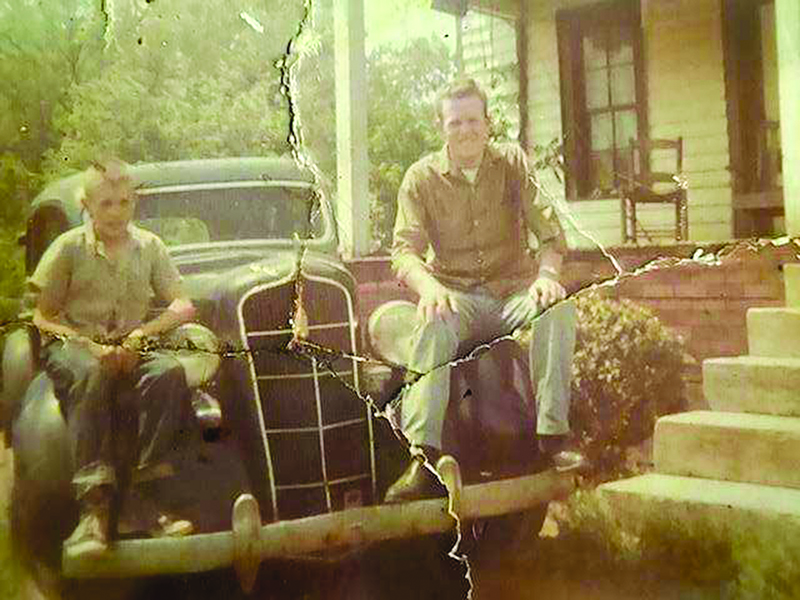

“He was a good-hearted guy,” he said. “We grew up on Rock Creek Road, Daddy had 180 acres and a farm there. We’d deer hunt together and fished the (Blue Ridge) lake. We both liked old cars. He bought Momma and Daddy’s old car that they bought new, a ‘56 Ford, and I’d ride to town with him on some occasions when he got old enough to drive.

“He was a good brother, real understanding, and he did things with all of us (siblings). He took good care of us.”

Ronnie said David went to work at Sunoco Paper Company in Atlanta when he was just 17, procuring a special worker’s permit because of his age.

“David would have graduated Gilmer High School in 1961,” Ronnie figured. “He’d been married and moved to Blue Ridge before he went in the Army. He got drafted in the early part of 1967. He hadn’t been over there but about a month before he got killed.”

Tommy Herendon said David and Carolyn Miller put off getting married because he thought he would get drafted. But then they decided to go ahead, and the draft notice came not long after they said their vows.

Jim was in the Air Force in the Philippines and Vietnam in 1966-67, and urged David to join the Air Force before he got drafted.

“I came back home in March or April of ‘67,” he said. “David had got married, and when I saw him I knew he was fixing to get drafted. I said, ‘Do not get drafted — you’ll go straight to the Army, straight to Vietnam. Join the Air Force or join the Navy.’ But he said he didn’t want to stay in four years, he wanted to go two years and get out. And he went, and you know what happened.”

Tommy said David “was an artist like you would not believe — deer, birds and cars of the future.”

“Nobody in the family could draw like him,” he said. “I’ve tried to draw something like a turkey, and it looked like a buzzard that got run over in the road. But the good Lord gifted him like that. He could have been a car designer, or whatever. There’s no telling where those drawings are now.”

Younger brother Greg pointed out he was just 5 when David was killed.

“I can vaguely remember him right before he went to Vietnam,” he said. “Daddy owned a store up in Cooper’s Creek (Fannin County) and I guess it was right before ‘Nam and he and another guy in the Army visited the store and they were in their khaki uniforms. Me and David and Ronnie were going somewhere, and I remember David carrying me on his shoulders. Those are the things that stick out in my mind.”

Conflicting reports

Ronnie said the last time he saw David was when he came by his home.

“He worked for me some, and came by at 5 in the morning and I paid him what I owed him,” he said. “Then they took him on down to boot camp.”

Tommy was on that final family trip.

“When we took David to Atlanta, I walked down the corridor with him to catch his flight,” he recalled. “I guess I was the last one in the family to see him alive.”

Ronnie said a soldier in the First Cav Division called him after David was killed.

“They were in the same unit, and he said they put my brother and two more guys on a bush patrol where they were watching this trail,” he said. “There wasn’t any trees, everything had been blown away. They put this new guy over them, and this guy killed my brother and two more men right together. It was friendly fire that killed him.

“They got that guy out of there and never saw him anymore. It was real sad. Everything David did, he tried to do his best at.”

Tommy also heard the report of an Army “boot” lieutenant (fresh out of boot camp) who was scared to death, heard something and started “spraying” the machine gun fire that killed David and two other men. Also, that the lieutenant was quickly shipped out of the unit.

But he also heard shrapnel from a grenade killed David.

“It was sad, but it didn’t matter how you got killed,” he said. “You got killed, didn’t you? Whether it was heroic, or whether it was someone like that that shouldn’t have been over there, it’s just sad.”

Greg also noted the conflicting reports about what happened to David. While acknowledging what an Army pal of David’s said to Ronnie about dying by friendly fire, he searched the division’s archives later as a First Cav member himself at Fort Hood, Texas. He also found on a website where a man in David’s unit kept a journal on what happened during his tour. On a page dated the day David was killed — Nov. 4, 1967 C the journal says three men, one of them named David Herendon, were killed together by a different account (see accompanying box).

Though young, Greg recalls the day they got the dreaded news at the family store in Cooper Creek.

“I was in the front of the store, there was a place I’d play on a little bank there,” he said. “ It was a green Army-colored Volkswagen with a white star on it. I remember seeing it pull up and two Army guys got out. They went in the store, and a minute later I heard crying. They came to tell us he’d been killed.”

Ronnie said their father had sold the Rock Creek property and moved in 1965 to Cooper’s Creek where they had the store.

“It devastated our family, it really did — especially my mother,” he said. “She didn’t live but about six years after he got killed; she never was able to get over it.”

Ronnie was 17 and “real close to David.”

“There wasn’t any good part about it,” he said of the news of David’s death. “There were some guys that knew David camped out on the creek hunting, and I remember going up there to tell them. Everybody was real sad to hear about it.”

Jim also said it was “a sad thing — of the six boys, I knew every one of them that got killed from Gilmer County.”

Tommy called Vietnam “one of the most ignorant wars we ever had.”

“But there were boys man enough to go fight it, weren’t they?”

Remembering an American Hero

Dear PFC David Mack Herendon,

As an American, I would like to thank you for your service and for your sacrifice made on behalf of our wonderful country. The youth of today could gain much by learning of heroes such as yourself, men and women whose courage and heart can never be questioned.

May God allow you to read this, and may he allow me to someday shake your hand when I get to Heaven to personally thank you. May he also allow my father to find you and shake your hand now to say thank you; for America, and for those who love you.

With respect, and the best salute a civilian can muster for you, Sir.

Curt Carter (posted on Oct. 25, 2013)

Source: vvmf.org/Wall-of-Faces/22708/DAVID-M-HERENDON/

An account of PFC David Herendon’s death

“ … I was shocked to discover that after the initial contact with my platoon, which I’ve described above, more grenades were thrown. First, three men were injured by grenades that came in at 0445 in the morning. Later that morning at 0515 hours, two grenades were thrown from the east into the western perimeter, and as a result, three of our guys were killed.

“Of these deaths, I knew nothing at the time, nor indeed until now. The dead were from another platoon: Robert Albertson, Jimmy Ray Baggarly and David Herendon.”

Source: Skirmish at the White Sand Dunes, by Richard Dieterle, vnwarstories.com/vn.SkirmishAtWhiteSandDunes.html

A road trip to remember

Before David Herendon was drafted into the Army and sent to Vietnam, he and Jim Logan took a long road trip to Florida. Both men needed to clear their heads after a tragedy in Cherry Log.

“I was dating his aunt, Mary Sue Whitener, when she was killed in a head-on collision with a tractor-trailer up on the old Cherry Log bridge,” Jim said. “After the funeral — probably the next day — me and him got in my ‘55 Mercury and went to Florida. We’d never been to Florida, and didn’t have much money — not enough to sleep in a motel, but enough for some gas and food, that’s about it.”

Jim had put recap tires on the car, and they started having flats.

“The boys (at the tire shop) wrinkled the tubes putting them on — tires weren’t tubeless back then — so we didn’t have enough money to spend for tires,” he recalled. “I talked to a guy at a service station, because I had worked at a Gulf station and ran a Texaco station at that time, and he let me patch the tube and fix the tires and didn’t charge me nothing. So we got all that fixed. We’d had two or three tires to go flat.”

When they got on down the road, they stopped at service stations to get cleaned up in the bathrooms.

“We drove all the way down the east coast, across the Tamiami Trail through the Everglades and back up the west coast back home,” Jim said. “We did a lot of talking.”